I was recently over at the Turchin Center for the Visual Arts in Boone, NC to see the exhibit “Lost in Form, Found in Line”. What a treat of imagery that was! Since I first was exposed to his work years ago, Motherwell has interested me; and then the more I read of him, my visual perceptions were confirmed that his work was not only attractive visually, but important conceptually. He was a thinker. I think he was also a paradox. For as was true amongst all the Abstract Expressionists after World War II, Robert Motherwell said that his work did not carry meaning. Yet his working process involved a lot of serious thought, considered musings, was often prompted by text. So his protestations about specific meaning often seemed disingenuous to me, the political correctness of his own time. Surely he was protesting the insult of casual viewers’ assumptions, e.g. “I see a duckie and a fishy”, when looking at his or anyone else’s non- representational work. He said that the subject of his work would emerge undirected “out of an interaction between myself, my I, and my medium.” But he also often admitted to big themes. One of his biographers, Jack Flam, says that Motherwell “wanted to create an art that would deal with the universal rather than the specific, yet be charged with feeling.” Motherwell often started with an idea. Then that idea got melded in the creative process, yet remained the idea/now feeling nonetheless, for he considered every mark, even buried under newer layers, part of the work’s important expressive history. Is this not then communication? Is this not then the embodiment, however shrouded, of some particular meaning?

I know for me, the first time I confronted abstract work at the Art Institute of Chicago when a teenager, I assumed immediately that it was coded language. It was not simple, but it was fascinating and even beckoning to me. See an example here. Now, I have been teased by an artist friend that I am looking for meaning everywhere. Actually, I have decided this is not such a foolish thing, for art is ultimately another human language. It is enculturated and wholly nuanced certainly, but it is a form of communication, I am convinced. Bird tracks on snow have meaning, even if the bird had no intention. How much more the marks of humans. The impetus to get out the materials and create starts with some kind of intention in mind, however small or unformed. Our marks leave a trail, and even trails that lead nowhere carry some inherent meaning.

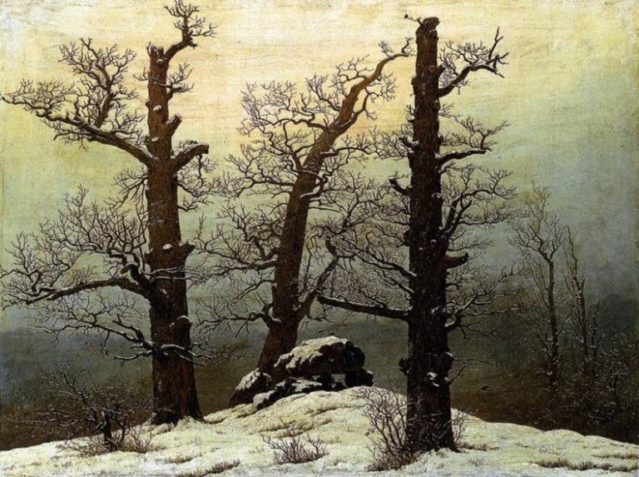

(above image is “Elegy to the Spanish Republic, No 110”, accessed off Bing)

On Hope-first thoughts

I am by genetic temperament, and fostered by early upbringing a pessimist; yet my work is said to be filled with hope! This to me, as I stand back and look is a complete surprise- “a huge contradiction,” I critique myself. Or, maybe better reckoned as an intervention – that is, there is something else that is working inside of me. Indeed, hope is the thing that gets me into the inks at all. Sometimes there is this inevitable agony – every artist I have ever spoken to attests to this agony. I love how David Bayles and Ted Orland summarize this in Art and Fear, “Basically those who continue to make art are those who have learned how to continue – or more precisely, have learned how not to quit…art is all about starting again.” So, there has to be hope that is dredged up from somewhere, or every artist would simply have no choice but to quit.

The Greeks considered hope dangerous. Indeed in the myth of Pandora, when the box was opened, there were released all the evils except one: that being hope. Hope was protected from release for its risky companion was delusion. However, in the end, Pandora had to release hope because otherwise humanity was filled with despair. To the Greeks then, hope must first have been considered an evil, which when weighed on the scales opposite despair, was bartered from evil to good.

Emily Dickinson succumbed to the risky business. And she heralds it this way, “Hope is the thing with feathers – That perches in the soul – And sings the song without the words – And never stops – at all.” I can identify with this thing that sings inside (and I didn’t put it there, I simply can’t make this happen). I share resonance with the words first penned by that serious and solitary woman from Amherst. It is an intervention, and it strikes me with awe. This is a core thing.

.