Yesterday an artist friend and I viewed an exhibit at Penland having to do with human perception. The artist/printmaker’s aim was to “dislodge humankind’s assumption of its centrality.” Her work was inventive, but left me empty. For, if we artfully (and alertly) remove humankind from the throne of mastery, what is being offered as a guiding replacement? Is that not a concern? I see, and I sense the implications; and I need more.

Yesterday an artist friend and I viewed an exhibit at Penland having to do with human perception. The artist/printmaker’s aim was to “dislodge humankind’s assumption of its centrality.” Her work was inventive, but left me empty. For, if we artfully (and alertly) remove humankind from the throne of mastery, what is being offered as a guiding replacement? Is that not a concern? I see, and I sense the implications; and I need more.

Most artists would recoil at my desire for a follow up plan. They would say they want to ask the questions, not provide any next steps. I counter, such posing is soberly irresponsible in an era of increasing trauma. The signs are all around us with record breaking hurricanes, earthquakes, fires, famines, and mounting armies. Artists are pretty good at noting some signs of the times, but have a poor track record at managing the seismic shifts. We need more than what artists (or politicians, or academicians) are laying out. So much is dying.

Christian philosopher Norman Wirzba observes that in Modernity, we rendered ourselves the Masters. The resultant cultural mind-set assumes that whatever sense there is in the world needs to come from us, and us alone (for God was dethroned long ago). That explains the dogged insistence that ‘we can still figure this out’, that ‘we can fix it all’; even while post-moderns are at least admitting that we have lost control. Few are looking at much beyond the walls of their own perception.

Blindness has been a human problem since long before Modernity. And Jesus had much to say about it. He knew the people around him (with working eyes, ears and brains) had a perception problem. He loved them anyway. He artfully spoke and performed signs right in front of all in a way that revealed who was actually perceiving. In fact, He said that the signs given by Him then, and in the future that He predicted, would not be grasped by the willfully blind. And even better than a prophet with perfect accuracy, better than any artist with probing questions, Jesus offered the next steps for the only sure way through the chaos. He’s Creator after all; and chaos was, in the beginning, just a working canvas.

artwork: Susan Goethel Campbell, detail of Ground No.5, 2017, Inverted, dried earth, dead grass

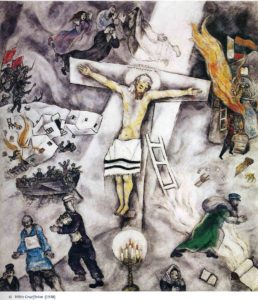

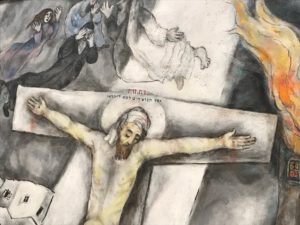

This piece startled me. Unmistakably Chagall, unmistakably modern, while being uncharacteristically direct as a narrative. I was already thinking about targets, about careful communication with the viewer (see last post). And then this. Chagall nails it. And he wants to make sure you can see it too.

This piece startled me. Unmistakably Chagall, unmistakably modern, while being uncharacteristically direct as a narrative. I was already thinking about targets, about careful communication with the viewer (see last post). And then this. Chagall nails it. And he wants to make sure you can see it too.

Jasper Johns’ 66 inch square piece is showcased at the Art Institute of Chicago and it jogged some thought. Johns’ intention when he made this and several other target images in the 60’s, was that viewers would see something familiar, “something the mind already knows” as a bridge or a catalyst toward further meaning. He was using the known to pry loose more that is not yet grasped.

Jasper Johns’ 66 inch square piece is showcased at the Art Institute of Chicago and it jogged some thought. Johns’ intention when he made this and several other target images in the 60’s, was that viewers would see something familiar, “something the mind already knows” as a bridge or a catalyst toward further meaning. He was using the known to pry loose more that is not yet grasped.

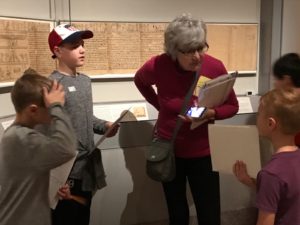

Here are just a couple fun shots. We investigated the motivations of artists through history. From Greek dynamism to the Egyptian funerary rules. From Renaissance perspective to Contemporary abstraction, the boys stayed engaged sketching, and questioning for 4.5 hours! Am I excited? The images give a glimpse of a most fun day. I think what was gathered here won’t soon be forgotten. I know I won’t!

Here are just a couple fun shots. We investigated the motivations of artists through history. From Greek dynamism to the Egyptian funerary rules. From Renaissance perspective to Contemporary abstraction, the boys stayed engaged sketching, and questioning for 4.5 hours! Am I excited? The images give a glimpse of a most fun day. I think what was gathered here won’t soon be forgotten. I know I won’t!

I’m not dressed for printmaking. Instead this one night, I attended an art opening of politically motivated art accompanied by an interesting lecture. The show’s juror,

I’m not dressed for printmaking. Instead this one night, I attended an art opening of politically motivated art accompanied by an interesting lecture. The show’s juror,

I struggle with my own voice in my work, living as I do in such a time of disintegration. I cannot make the work of my hands “say” what I hold in my heart so often. It is not my goal to be literal, but it is a desire to lift the viewer’s eyes. A friend of mine who is a photographer, grieving deeply over the death of her husband is now doing the best work of her career. We talked of this: why are we doing this work, this searching with images? Is it meaningful, is it what we “should be doing”? We got this far in our discussion: this work is an exploration into JOY. This expression is as fleeting as a sunset and as mysterious as a bird’s flight, but it is necessary, if even just for us. I have some ability to look, and to craft. Maybe through the work of my own hands others will see meaningfully also. For this, I keep on.

I struggle with my own voice in my work, living as I do in such a time of disintegration. I cannot make the work of my hands “say” what I hold in my heart so often. It is not my goal to be literal, but it is a desire to lift the viewer’s eyes. A friend of mine who is a photographer, grieving deeply over the death of her husband is now doing the best work of her career. We talked of this: why are we doing this work, this searching with images? Is it meaningful, is it what we “should be doing”? We got this far in our discussion: this work is an exploration into JOY. This expression is as fleeting as a sunset and as mysterious as a bird’s flight, but it is necessary, if even just for us. I have some ability to look, and to craft. Maybe through the work of my own hands others will see meaningfully also. For this, I keep on. Amid the noisy machines, flashing tv screens and the running track, there is a window at my fitness center. It is a glass block section that scatters light into the space where we work. Everyone inside has an individual training plan going on. There’s sweat, determined looks, clocks, and all around the sounds of metal clanking. I was tromping along with my earbuds locked into a current-events podcast when I got stopped by this view. This was greater news.

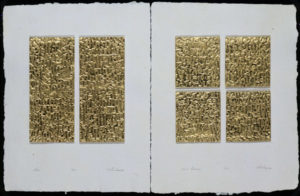

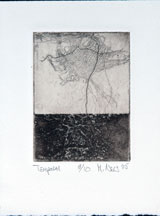

Amid the noisy machines, flashing tv screens and the running track, there is a window at my fitness center. It is a glass block section that scatters light into the space where we work. Everyone inside has an individual training plan going on. There’s sweat, determined looks, clocks, and all around the sounds of metal clanking. I was tromping along with my earbuds locked into a current-events podcast when I got stopped by this view. This was greater news. Trajectories that meet at a single point are called a convergence. Lines become a single point of intersection, and these places are rare. Rare in life, and I think intriguing in art. This image is a detail of an etching I did several years ago. The piece is called “Temporal”. The idea to me was just the wonder in the slowness of time. As things look random, time is what gives us a chance to view the quiet emergence of so much that is important: the blossoming of fruit, the maturing of character, the perfect development of every longed for thing. And in this waiting there can be great mercy as a trajectory moves toward fulfillment.

Trajectories that meet at a single point are called a convergence. Lines become a single point of intersection, and these places are rare. Rare in life, and I think intriguing in art. This image is a detail of an etching I did several years ago. The piece is called “Temporal”. The idea to me was just the wonder in the slowness of time. As things look random, time is what gives us a chance to view the quiet emergence of so much that is important: the blossoming of fruit, the maturing of character, the perfect development of every longed for thing. And in this waiting there can be great mercy as a trajectory moves toward fulfillment.