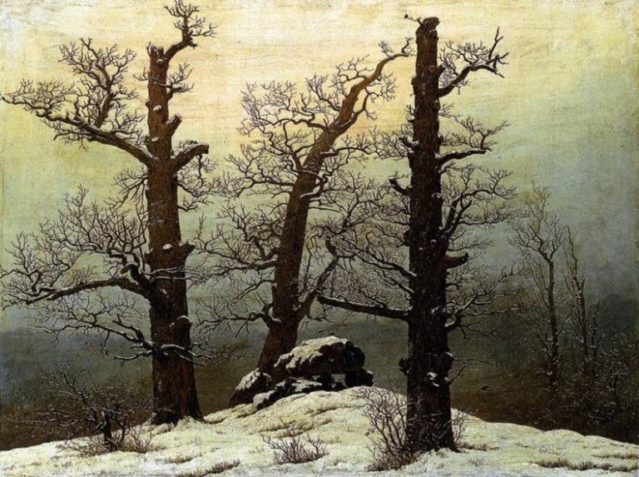

I offer two images today that I did not make happen. We were on a hike after two solid work weeks. We were aiming to take a rest, some re-creation, to gather some beauty. I could show the images from the waterfalls, or the lovely plants along the path, of my grandson’s smile, of the big Lake Superior’s sunset. . . a feast of beauty; but it is these shots that really deeply spoke to me. They are not even pointing to anything concrete. They came unsolicited into my iPhone. The device must have remained on, while inside my pocket in between my grabbing it for a shot. Somehow the little wonder of my phone kept clicking away and there were maybe 20 of these frames that day, some intensely beautiful. I am removed therefore from the selecting of these. I just get to enjoy them. The shimmer and the glimpsing of light through the fabric of my nylon pants, is like a gift I did not expect, as I walked the path.

Around the same time I was reading Frederick Buechner’s “Magnificent Defeat,” and also pondering the words of Peter’s first letter to struggling Christians. Rich words those, from two mentors. Peter encourages hard choices in hard places, but does not assume this can ever be done alone. He shows the enabling example we have, he tells of the rewards coming and he reminds that it is possible “if you have tasted the kindness of the Lord.” I have been holding onto the sweetness of that phrase and what it points to, then seeing the evidence right inside my pocket.

Think about it, your body is a very dark place on its own. When scopes go into our bodies they must bring their own light, like miner’s lamps, to be able to see anything. When bodies are on surgical tables they are dark chasms until the surgeon’s knife cuts open flesh and the huge lights over the table light up what was hidden and all closed in. We only see these things because our eyes have taken in light first. This is simply true, and the physical is a signal/type for what is more important, the spiritual. Looking into someone’s eyes is often so intuitively instructive as to whether there is any life or light in there. According to Jesus, for any light to be inside us, we have to let it in, we have to allow our lamps to be lit. We cannot come forth with light on our own. Light was the 1st creative accomplishment in Genesis and it comes forth from God. This is basic though I stumble over it.

Think about it, your body is a very dark place on its own. When scopes go into our bodies they must bring their own light, like miner’s lamps, to be able to see anything. When bodies are on surgical tables they are dark chasms until the surgeon’s knife cuts open flesh and the huge lights over the table light up what was hidden and all closed in. We only see these things because our eyes have taken in light first. This is simply true, and the physical is a signal/type for what is more important, the spiritual. Looking into someone’s eyes is often so intuitively instructive as to whether there is any life or light in there. According to Jesus, for any light to be inside us, we have to let it in, we have to allow our lamps to be lit. We cannot come forth with light on our own. Light was the 1st creative accomplishment in Genesis and it comes forth from God. This is basic though I stumble over it.