The journey of Moses leading the Hebrews out of slavery and into the land has informed some recent visual work. There’s a curious episode with water coming out of a rock that strangely happens twice: once at the beginning of their sojourn and then again right before they enter the land promised them. Both times the people are thirsty and near riotous. Both times God gives Moses instruction. Both times Moses needs to take action. But the action the first time is to strike the rock and the second time Moses is only to speak to it. It’s a fascinating repeat with an important distinction.

The journey of Moses leading the Hebrews out of slavery and into the land has informed some recent visual work. There’s a curious episode with water coming out of a rock that strangely happens twice: once at the beginning of their sojourn and then again right before they enter the land promised them. Both times the people are thirsty and near riotous. Both times God gives Moses instruction. Both times Moses needs to take action. But the action the first time is to strike the rock and the second time Moses is only to speak to it. It’s a fascinating repeat with an important distinction.

Patterns and parallels catch attention. When something repeats, be it sound or sight, there’s a resonance of some sort. There’s potential being built. We’re hardwired, I think, to be alerted when there’s a repeat. Curiosity gets engaged—something intentional seems to be happening. When a strange chirp repeats I know it’s more than random, so I go looking for it. When the 2nd plane hit the towers, there was universal recognition that we were no longer dealing with accident. I watched that 2nd plane hit, and was startled at how instantly that repeat was a game changer of terrifying consequence. Everyone who saw that knew instinctively.

I was in a workshop this past week with an artist who’s done a lot of reading about how our brains perceive and then recognize. He posited that we’re all visual learners; we all take in data and start making connections. But it’s in the investigating where real learning gets sealed in our memory. And that takes some time and consideration.

So back to Moses, why was he tasked to strike the first time but only speak the second? For me this parallel of two rock stories is really pregnant, there’s more here. Moses had learned about striking. And by the end of the long wilderness journey he was oh-so ready to strike again. Why twice this rock thing then at these completely different times/locations? There’s nothing particularly distinguishable about the rocks in either episode. What is God teaching here in the narrative? It’s not random. There’s much that is not explained in the text, but some particulars are very clear. Needed water came out of rock both times and the people were sated. God gave words, both times. But Moses failed miserably at the 2nd rock because he applied an old instruction to the parallel. At the repeat episode, he was only to speak to the rock. Most find this biblical episode harsh, as if we gift-receivers have any high ground for critiquing the gift-giver. But God poured out that gift of water—both times, in spite of Moses’ fail. I am wondering if the parallel isn’t more deeply meaningful than our memories can yet gather in.

Moses personally addresses God later as “The Rock!” and he does so with overflowing praise at God’s perfection in all His ways. Moses had learned these ways of God, even through severe disappointment. I am not a good listener, so this story stills me. I am an activist who gets angry easily, therefore my empathy for Moses is pretty deep. But deeper still is the provision from the water giver, unseen but present within each of these common rocks. The first time the rock was to be struck. The second time: only spoken to.

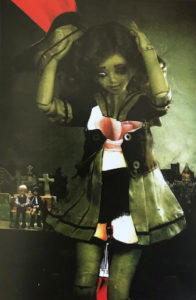

But then, I noticed a diminutive collage, chosen as a favorite by the museum staff, “Art to Stop Traffic: What Mercy Requires of Us”. The piece is only 5”x 3.5”. This submission is a poignant contrast, rendered from found images, paper, pen and pencil. The value and color contrast is immediately obvious, but peering closer one sees the uncomfortable juxtaposition of plastic expressions, skin color, garish lighting, things hidden and things exposed.

But then, I noticed a diminutive collage, chosen as a favorite by the museum staff, “Art to Stop Traffic: What Mercy Requires of Us”. The piece is only 5”x 3.5”. This submission is a poignant contrast, rendered from found images, paper, pen and pencil. The value and color contrast is immediately obvious, but peering closer one sees the uncomfortable juxtaposition of plastic expressions, skin color, garish lighting, things hidden and things exposed. Yesterday an artist friend and I viewed an exhibit at

Yesterday an artist friend and I viewed an exhibit at

I don’t think it is a very pretty piece, and therefore, to me, all the more true.

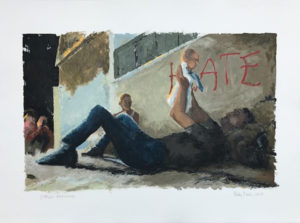

I don’t think it is a very pretty piece, and therefore, to me, all the more true. I plotted this sketch onto a full sheet of Arches oil paper, conscious that getting the value structure right was going to be pretty critical before color choices. Also, since my skills are not in the arena of literal portrayals, I needed a visual roadmap of sorts. I usually don’t do figures, but this one was persistent for attention.

I plotted this sketch onto a full sheet of Arches oil paper, conscious that getting the value structure right was going to be pretty critical before color choices. Also, since my skills are not in the arena of literal portrayals, I needed a visual roadmap of sorts. I usually don’t do figures, but this one was persistent for attention. My hope is that in the venues where this might be seen that people may be moved to awaken, to care just a little, to not be able to forget.

My hope is that in the venues where this might be seen that people may be moved to awaken, to care just a little, to not be able to forget. A good portion of my work is an intuitive response, rapidly laid down. This does not mean that the result seen on paper was altogether quick, though if you had watched this piece and others being birthed you might think so. What is visible is an end product of a long term simmering from my mind, spirit and body. The thoughts that collide toward and then into a particular working session, the prayers that have been raised and linger as I craft, and the arms and legs that labor this forward are mine.

A good portion of my work is an intuitive response, rapidly laid down. This does not mean that the result seen on paper was altogether quick, though if you had watched this piece and others being birthed you might think so. What is visible is an end product of a long term simmering from my mind, spirit and body. The thoughts that collide toward and then into a particular working session, the prayers that have been raised and linger as I craft, and the arms and legs that labor this forward are mine. Most all of us, living housed in our bodies, have functioning eyes. I love my eyes, and thank God for them; for with them I notice expression that tells me so much more than words. With them I can work with my hands at all kinds of things. With them I can apprehend beauty. And then with them I can lower my lids and signal the whole of my body to rest.

Most all of us, living housed in our bodies, have functioning eyes. I love my eyes, and thank God for them; for with them I notice expression that tells me so much more than words. With them I can work with my hands at all kinds of things. With them I can apprehend beauty. And then with them I can lower my lids and signal the whole of my body to rest.

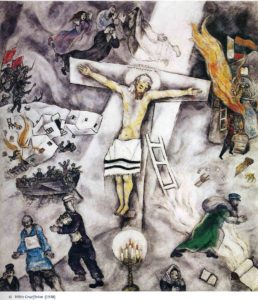

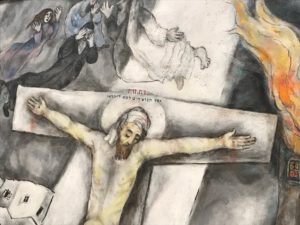

This piece startled me. Unmistakably Chagall, unmistakably modern, while being uncharacteristically direct as a narrative. I was already thinking about targets, about careful communication with the viewer (see last post). And then this. Chagall nails it. And he wants to make sure you can see it too.

This piece startled me. Unmistakably Chagall, unmistakably modern, while being uncharacteristically direct as a narrative. I was already thinking about targets, about careful communication with the viewer (see last post). And then this. Chagall nails it. And he wants to make sure you can see it too.

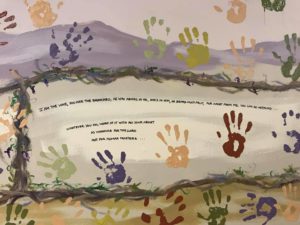

Another friend and I worked this week on the huge mural project we started last year. It too is a continuum. It starts at the beginning of historical time and ends where the kids in the program we are serving, can look into a mirror. All along the way are emblems of the grand story, punctuated by avatars of the very kids who walk this hallway after school. We’re hoping to lift their vision even as we are lifting our own.

Another friend and I worked this week on the huge mural project we started last year. It too is a continuum. It starts at the beginning of historical time and ends where the kids in the program we are serving, can look into a mirror. All along the way are emblems of the grand story, punctuated by avatars of the very kids who walk this hallway after school. We’re hoping to lift their vision even as we are lifting our own. I’m not dressed for printmaking. Instead this one night, I attended an art opening of politically motivated art accompanied by an interesting lecture. The show’s juror,

I’m not dressed for printmaking. Instead this one night, I attended an art opening of politically motivated art accompanied by an interesting lecture. The show’s juror,