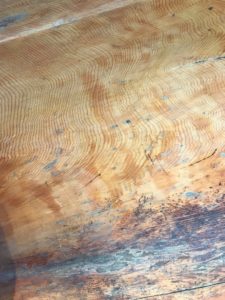

The floor of a red cedar canoe, in the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia quietly testifies to its own story. Once standing tall and alone in a rain forested wood fringing the Pacific, it was scope-ed out then heavily laid down. Done. Cut off from its nourishment; it was then gouged, steamed and stretched by the hands of others. Soon it was deemed seaworthy, buoyant and bearing. It was now a thing, not a living thing. This lovely tree was un-noticed until it was found useful for the ends of others. It is said that the first nation Indians were careful with trees, making only single slits in bark to preserve a tree’s life.

The floor of a red cedar canoe, in the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia quietly testifies to its own story. Once standing tall and alone in a rain forested wood fringing the Pacific, it was scope-ed out then heavily laid down. Done. Cut off from its nourishment; it was then gouged, steamed and stretched by the hands of others. Soon it was deemed seaworthy, buoyant and bearing. It was now a thing, not a living thing. This lovely tree was un-noticed until it was found useful for the ends of others. It is said that the first nation Indians were careful with trees, making only single slits in bark to preserve a tree’s life.

But what of this tree? Are we to consider it a sacrifice? Are some sacrifices worthy? And by whom?

I could show you other photos: of the carved yokes that adorn the gunnels, of the painted designs: the brands of ownership. But to me these whispered lines of life are the most authentic. It’s a silent recording of the lively passing of years. In these is seen the marks of weather and growth of push and pull when the tree was still responding on its own.

Time is a slow and certain mover. It is gentlemanly. It is more reflective of the Maker of trees than are the hands of many men. In this testament of silent marks I take comfort, even as the tree itself has been laid low. Emily Dickinson resolves the sadness by saying “let months dissolve in further months—and years –exhale in years—“*

I will let this be then, except for reminding us here. For in these marks I see a most particular record of days not forgotten.

*poem #690, Source: The Poems of Emily Dickinson Edited by R. W. Franklin (Harvard University Press, 1999)