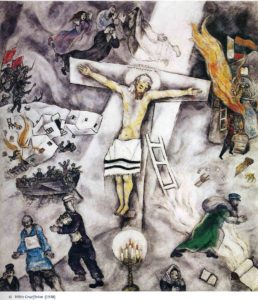

This piece startled me. Unmistakably Chagall, unmistakably modern, while being uncharacteristically direct as a narrative. I was already thinking about targets, about careful communication with the viewer (see last post). And then this. Chagall nails it. And he wants to make sure you can see it too.

This piece startled me. Unmistakably Chagall, unmistakably modern, while being uncharacteristically direct as a narrative. I was already thinking about targets, about careful communication with the viewer (see last post). And then this. Chagall nails it. And he wants to make sure you can see it too.

Normally Chagall’s work is typified by dream like, color-filled reflections from his charmed Lithuanian childhood. The artist grew up in a happy Hasidic community, which shaped his worldview. “Ever since early childhood, I have been captivated by the Bible. It has always seemed to me and still seems today the greatest source of poetry of all time.”

But by the end of the Second World War, his hometown, of 240,000, Vitebsk, had been decimated with only 118 survivors. The year for this crucifixion piece was 1938 just after the Nazi’s raided synagogues in Kristallnacht, “Night of the Broken Glass.” And so the artist has placed Jesus right in the middle between advancing Communists on the left, and German destruction on the right. Above the cross are lamenting Jews, including one of Chagall’s characteristic prophet figures. The mourners are reacting to events even as they are clustered before the speaking prophet. This is in contrast to the Jews on the ground, below the cross who are fleeing every which way. One wears a sign “Ich bin Jude”. The dying man on the cross is obviously also a Jew, wearing only a Tallit or prayer shawl.

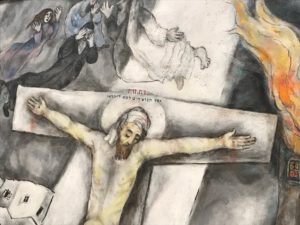

Too easily is Jesus dismissed in any age. Chagall in his age makes a distinct effort to point him out. The dying Messiah is the focal point compositionally midst everything that distracts. The light from the candelabra is missing one lit branch, while light from way above the prophet illuminates the prophet’s call to listen. And so no one can miss it, Chagall letters it out in Hebrew: “Jesus Christ is King of the Jews”.

This is not Chagall’s first attempt at a crucifixion. Such a sign is difficult for any Jew. But the events in Chagall’s history, both personal and global, demanded an ultimate statement of conviction. There is no question but that this is deeply felt, and as is so often the case with Chagall: picturing hope. In case that is too abstract an assumption, let the artist speak for himself: “For about two thousand years a reserve of energy has fed and supported us, and filled our lives, but during the last century a split has opened in this reserve, and its components have begun to disintegrate: God, perspective, colour, the Bible, shape, line, traditions, the so-called humanities, love, devotion, family, school, education, the prophets and Christ himself.”

‘My painting represents not the dream of one people but of all humanity’.

Listen to how a contemporary singer-songwriter has tried to illuminate this.

I recently came across another clarified statement from the writer John Updike, reflecting on the resurrection which followed this death of the Jew Jesus:

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

analogy, sidestepping transcendence;

making of the event a parable,

a sign painted in the faded credulity of earlier ages:

let us walk through the door.

Thank you, Mary.

with thanks to the only God who went to such lengths for us! Just found this from Edward Shilito:

“The other gods were strong, but Thou wast weak;

They rode but Thou didst stumble to a throne;

But to our wounds only God’s wounds can speak, and not a god has wounds but Thou alone.”