This month, I was arrested by a painting. It was among many other works in a fine exhibit the Germans brought to Beijing, housed in the newly constructed National Museum. The exhibit, covering several rooms, highlighted the “The Art of the Enlightenment.”

The Enlightenment is known by historians as a time of great scientific discovery in the West, and known by art historians for its grandiose swings away from the patronage and parochialism of the Church to a search for higher human ideals for source material. Artists explored themes and styles to authenticate their aims. From this time we get the beginnings of brilliant graphic political satire (Hogarth and Goya), a revisit to the ancient mythologies of Classicism (Delacroix, Titian), and the development of Romanticism and its reach to the landscape.

It’s easy to see how the Chinese, though not as inclined to the former two aspects of this time in Western history, would certainly resonate with the importance of the landscape. Enlightenment artists thought they had discovered “the sublime,” when all along Chinese landscape artists had been musing on those depths for centuries. There was a whole room dedicated to these sublime European landscapes and the room was being well visited.

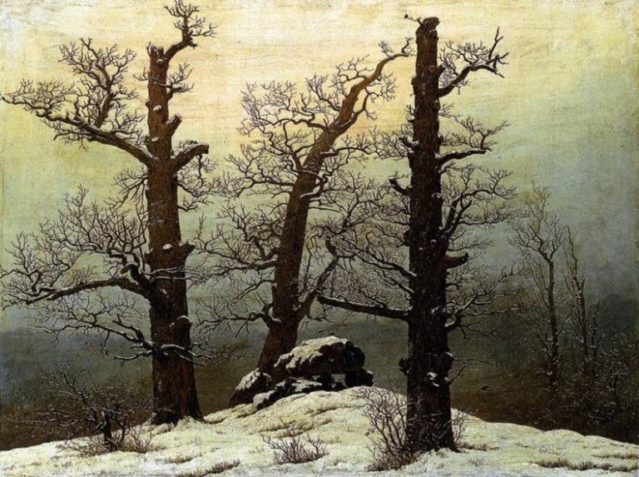

In this room I found a small oil—“Dolmen in the Snow”—by a German I knew little of, Caspar David Friedrich. This piece is simple and profound. The foreground is foreboding, indeed a dolmen is a burial place. The three trees in the painting appear dead as well, though likely dormant from winter. The central tree is leaning and is closest to the dolmen. There has been much cutting of branches of the other two trees. But of the fingerlets of branches we see, they are all reaching upward.

Snow blankets this quiet scene, and there are no figures except a lone bird whose position indicates we are located in a high place. The starkness of contrast between this dismally yearning and empty scene and the sky is what stopped me. The sky is luminescent and beckoning, warm and enveloping/changing the entire effect. Apparently Friedrich intended this piece (as with some of his other works) to be a defense of his faith as a Christian.

Friedrich was living at a time when to be overt about one’s faith was “uncool” according to the groupthink. So he stays under the radar but uses his art to symbolize what is in his heart. It still speaks. In fact, later artists look to some of his work as the beginning of symbolism.

The last room of this entire exhibit was a jump into the Modern/Postmodern era with a few selections: a portrait by Andy Warhol, some abstracts and a sculpture by Beselitz, and a video by Joseph Beuys. My sense is that the curators were wanting to show the end result, to date, of the aims of the Enlightenment. In their Western conceit they think that the end is always going to be better than the beginning, that tolerance really is the highest ideal, that meaninglessness and self-mythologizing is very deep.

I think the Chinese observers will likely have more an objective detachment and consider this end otherwise. The art speaks for itself. For me, I’m back in that landscape room.