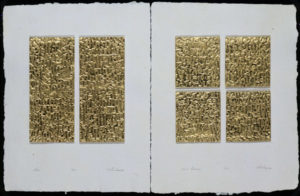

The idea (last post) of God writing has had me musing. For text marked into pieces of ground is kind of a current thing. Detailed is just a fragment of a painting I saw last week in a gallery in Asheville, NC. The hand is artist Carol Bomer’s. The marking of words gives direction not only visually but conceptually. One takes in the whole of this dark piece as it envelopes your eye-space, but then the writing captures your focus.

The idea (last post) of God writing has had me musing. For text marked into pieces of ground is kind of a current thing. Detailed is just a fragment of a painting I saw last week in a gallery in Asheville, NC. The hand is artist Carol Bomer’s. The marking of words gives direction not only visually but conceptually. One takes in the whole of this dark piece as it envelopes your eye-space, but then the writing captures your focus.

We think this marking into media is avant-garde. Search and you’ll find lots of new and inventive uses of text. But the idea is as old, really, as the hills. At the Mountain called Sinai, the finger of God etched his law into two pieces of rock. This inscribing of text was not Moses’ idea. The finished tablets were not Moses’ handiwork. The entire initiative was God’s. Moses was only the invited mediator. (There are many questions here: If God is God, why did he even need to use a finger? Why two tablets, why not 10, why not one? Why was any mediator needed? Why were words needed? Were the Hebrews, recently slaves, literate? Was the marking that God used common Egyptian?) Back to what’s clear in the story: Moses responded as he was asked. He picked up the rock slabs and brought them down from Sinai to the awaiting tribes.

Think about this even if you don’t know much more. The Hebrew text makes it plain that God’s own finger made visible markings on 2 pieces of mountain rock. He communicated, from His otherness into man’s space. This was one directional. He selected a means that was legible, tangible and understandable. Then came the history of man’s response to that specific communication.

Besides the later episode in Babylon with the mysterious hand (previous post), there is no other hint of God Himself writing in the whole of the Hebrew Bible.

Fast forward to what is called the New Testament or that part of Scripture that tells of Jesus’ arrival and the revolution he brought. There is only one recorded episode of Jesus writing. The story is found only in John’s telling of events. The context is a test. Religious lawyers drag a woman before Jesus. Having just been caught breaking one of the laws on Moses’ tablets, she stands vulnerable and shamed. These prosecutors figured shrewdly. With the evidence before them all, Jesus would be trapped. If gentle Jesus dismissed the woman, he would be sanctioning the breaking of God’s law, and therefore could be correctly branded as a false prophet. If Jesus, a righteous Jew, followed the law and condemned the woman to be stoned, the religious testers would be vindicated, their power enhanced with Jesus as their pawn. Jesus turned the tables, and this is how he did it.

He stooped down and used his finger to write something into the dirt.

He stooped down and used his finger to write something into the dirt.

“Doesn’t this man have eyes and ears?” “Doesn’t he understand the violation?” The accusers mocked and persisted, pointing their own fingers wildly. The noise around this huddle grew louder. Only one finger was writing. Then, remaining silent, Jesus stooped down a second time into the dust beneath them and wrote again. (What did he write? Could they all see it? Why a second time? In the angry heat, how could dusty marks be any tactic?) Whatever he wrote there is not explained, but what is clear remains. What he did in the dirt was enough to silence them all. One by one, the angry men put down their stones and walked away.

What strikes me is the symmetry in both these singular stories. When Jesus writes he is likely referencing the writing of God. The fact that he does it twice, and quietly is poignant. The law God wrote was left intact that day. But now one, with her feet still there in the dust, saw the final mediator. Failure had constrained them all to face Him who alone had authority to bridge the gap between a history of shattered lawbreakers, and the Law giver Himself. He could only do that if He had fingers, eyes, ears, a knowledge of his people’s mandate intersected with a heart of compassion.

The idea (

The idea ( He stooped down and used his finger to write something into the dirt.

He stooped down and used his finger to write something into the dirt.